anvajo: Hello Mr. Seper, thank you for the opportunity to interview you today. Shall we start with a short introduction?

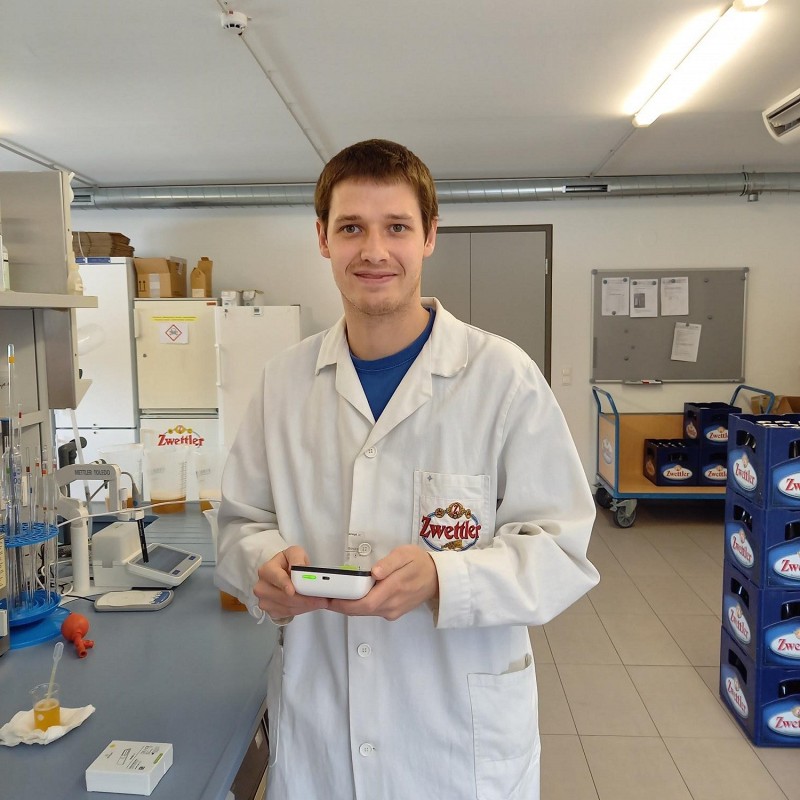

Johannes Seper: I'd love to. I'm Johannes Seper and I started my brewery apprenticeship in 2015 and finished in 2017. I currently work at the Zwettler private brewery, which has been in the hands of the Schwarz family since 1890. The brewery itself has been around since 1708 and we have two breweries with two different locations with a total output of 210,000 hectolitres. That's about 195,000 hectolitres of beer and about 15,000 hectolitres of non-alcoholic drinks such as lemonades. This means that we have a total of 14 different types of beer on the market, as well as three of our own lemonades.

anvajo: That's quite a lot! How many employees do you have?

Johannes Seper: We have 125 employees in the whole company, plus minus, of course.

anvajo: So it is a larger company after all. What exactly are your tasks?

Johannes Seper: Since September 2018, I have been working in the laboratory, where quality assurance plays a big role. There are two other employees who support me in the laboratory on an hourly basis, but I am mainly responsible there. In our lab, the entire process of monitoring takes place, from malt delivery to fermentation and yeast propagation to bottling, and of course the automation of these processes. Until now, we did many things manually and stumbled across the R-300 in search of more automation.

anvajo: That's good to hear. Before we talk about the fluidlab R-300, would you perhaps like to give us a brief insight into the processes involved in brewing beer? What are the steps that must be gone through?

Johannes Seper: Sure. To start a brewing process, you always begin by malting the barley. In the past, breweries used to do this themselves, but nowadays they buy it ready-made from malting plants, which then process the barley into malt. This means that our first step in the brewery is to mix the purchased malt with water in the so-called mashing process, in which certain temperature levels are maintained so that enzymes convert the starch contained in the malt into sugar.

After mashing comes the so-called lautering. During this process, the husks of the barley act as a sieve and separate the liquid, called beer wort, from the solids, the spent grains. The spent grains are sold to farmers as animal feed. The wort is then boiled, and hops are added. After boiling, the wort is cooled to about 10°C for fermentation and aerated, then yeast is added in the cellar. This yeast is fundamental to the beer because it ferments the sugars into alcohol, CO2, and heat. After fermentation, the beer is cooled again. This is followed by a storage phase of three to four weeks. It depends on the type of beer whether it is filtered afterwards or not. Finally, we fill it into glass bottles or barrels.

anvajo: And how is this process monitored in the laboratory? Or do you have certain parameters that are relevant?

Johannes Seper: Of course. We have several parameters that we must observe during the production of beer. One important parameter, for example, is the sugar content in the wort. This is determined at the end of the boil in the brew and must remain roughly the same so that we know that the quality of the beer will always be consistently good.

To explain: at the end of the boiling process, the wort will have a certain sugar content, the so-called original wort in beer. This is similar with wine, for example, which should also have a certain sugar content at the end of the process. However, while with wine it is desirable for the sugar content of each batch to be different at the end of production, the opposite is the case with beer: with beer you want to keep the quality at a constant level, which means that the sugar content of each batch must be more or less identical at the end of the process. That's why they say beer is the most difficult drink to produce in the world.

Also important is the pH value, which we check regularly. Together with the original wort, it is one of the most important parameters. During fermentation, the residual extract and the pH value are measured daily to control the fermentation process. This is where the fluidlab R-300 becomes interesting for us, because with this small device you can determine the cell count, i.e., also how many yeasts are contained per millilitre of young beer.

anvajo: If I may hook in there for a moment: What did you use for this before the fluidlab R-300?

Johannes Seper: The microscope and the Thoma counting chamber.

anvajo: Okay, so you counted it by hand with a microscope. And now you have switched to the fluidlab R-300 because you want to push the automation I mentioned earlier?

Johannes Seper: Exactly. The fluidlab R-300 is faster and I can simply take the device with me for these processes because it is so handy. I no longer have to bring a sample to the lab for every measurement, but I simply have the device with me when I add a new yeast, for example. That way I can measure it directly at the bottom of the tank, which of course has considerable advantages.

anvajo: That's really practical, of course. It's difficult to do that with a conventional microscope. Does that mean that you will permanently count the yeast with the fluidlab R-300?

Johannes Seper: Yes, definitely. The fluidlab R-300 makes my daily work easier, so I wouldn't want to be without it in my lab.

anvajo: That's really nice to hear, of course. Did you notice any other things in the comparison? For example, in terms of the reliability of the results? Were you satisfied with the quality?

Johannes Seper: The official method of counting is not relevant for us for process monitoring because it is too time-consuming. If you do it officially, you would have to draw an average from several values. However, the data of the fluidlab R-300 are satisfactory for our processes and parameters even without elaborate averaging, because I usually only need approximate data and not very precise ones. However, we can still say that the statistical accuracy in our laboratory has been increased with the fluidlab R-300.

anvajo: That's great feedback. Did you ever have problems with the fluidlab R-300?

Johannes Seper: Yes, we had a problem internally with the anvajo datalab, the program that transfers the images and data. The W-Lan has to be stable for that to work. In the end, we were able to solve the problem with anvajo's support and are now very satisfied.

anvajo: That's good to hear! I have one more small question to conclude our interview: Is there a beer in your product range that one should definitely try?

Johannes Seper: Absolutely! There are many varieties that I like very much, but I am also a big fan of our main beer, Export. It's a classic Austrian Märzen beer with a great malty taste, but also a strong hop bitterness. The newest variety in our house is the "Schwarze", which is a classic dark beer and is now also one of my favorites. I'm happy to recommend both of them!

anvajo: Then we'll definitely have to try them! Thank you very much for the exciting insights into the topic of the brewery.